Let the leopards live, please

by, Muhammad Atif Aleem

In Galiat, the mountainous region in northern Pakistan, it is not very uncommon for a clamour to suddenly arise, disturbing the calmness of the whole village. Someone shouts in the local Potohari accent:

“Pakro cheetah maari bakri ghinni gia je” (Help, the leopard has taken away my goat.)

The hysterical shouting awakens the whole village, and hearing it, every adult male arms himself and rushes towards the house. The panicked villagers may spend a couple of nights guarding the pathways leading to the village. They may even choose to rush after the beast in the not-so-thick jungle. Usually, the much cleverer beast manages to escape, but sometimes she is caught and killed.

Every villager living in the middle of this fascinating landscape has his own haunting tails that involve only one perpetrator: the common leopard.

No matter how shy and elusive this beast is, the common leopard, over a period of time, has been a nightmare for the whole region because of livestock depredation in the human settlements on the outskirt of the forests. Despite living with a vague and rather confused identity, she remains vividly alive in the myths and memories of the people with whom she shares the same landscape, the same heritage and the same cycle of life. Knitted into the same fine fabric of nature, both creatures are related to each other.

Gone are the days when leopards were content with the reasonable size of prey offered by the jungle, and resultantly humans could fearlessly tread there. The region didn’t know such thing as a conflict between humans and leopards. Back then, the local population was thin, the pressure on the jungle resources was not beyond limits and the local communities had well defined rights to use these resources. Moreover, in spite of their dependence on natural resources, the local population was careful enough to maintain a perfect equilibrium between its needs and forest resources.

During the gentle summer evenings, the fumes of smoke emitting from the rooftop chimneys in the area remind us of the century’s old relationship based on coexistence and harmony between humans and their non-human neighbors. But, within a few decades, factors like chronic human greed, gross mismanagement, instinctive callousness and increasing pressure of human population on the forests have ruined these fragile relationships.

Historical records reveal that until the Colonial era, the region was rich with an immense variety of fauna and flora in the ecosystem of the region. Then, it happened to be an echoing jungle with a countless diversity of wildlife. A great range of big animals could also be found there. Even big cats; including lions, tigers and cheetahs were not uncommon in the vegetation of Galliat and its surrounding areas. Now, all have gone with the wind and we are left with one, the common leopard. Now they are on the verge of extinction in the unprotected areas of the region.

Normally, found at a high altitude, leopards are the most adaptable predators with a very flexible food choice. What she requires is a sizeable prey base in her territory, a secured and sufficient home range and sufficient forest cover for hunting and survival. But, despite their adaptability, the leopard population in parts of its natural habitat is declining due to scarcity of the mentioned elements.

It is only the Ayubia National Park in Galliat, which as a national park offers safety and conservation to the carnivore, but its 3312 hectare area has proven insufficient for their well being. Similar is the case with the nearby Lasora National Park in Azad Kashmir region.

With rapid growth in human population, the increasing use and misuse of forest resources even inside the protected area has become a potential threat to the biodiversity of the region. There are some known threats to the ecosystem and the wildlife of Ayubia National Park, some of them are the rising mountain of litter being spread by tourists and hotel owners, illegal grazing, collecting of fodder, woodcutting and cultivation by local communities. But, the most serious threat to the whole chemistry of the area is nothing but human greed.

The whole area is witnessing an unprecedented wave of ill-planned development, mainly aiming to serve the vested interests of many influential local people. Trees are being cut and burnt ruthlessly. Land is also being acquired for construction of new residential colonies, road networks and cultivation purposes. By courtesy of ineffective management of the local administration, the illegal timber and builder mafias are operating unchecked. That all is contributing to deforestation, degradation and fragmentation and is also causing a further retreat of the fauna from its natural habitats.

So, precisely, the unending conflict between the humans and leopards can be attributed to man’s ever increasing greed that is pulling him to ravage the shared resources of the forests.

Much of the animals the leopards preyed on have disappeared completely. Therefore, they turn to human settlements when they are hungry/ Obliged with an easy choice, the trapped and starved beast spreads her home range to the extent of the nearby villages to satiate her hunger. And, when a predator finds its way to easy, domesticated prey, she starts her depredation on the human settlements.

The human-leopard conflict is characterised by an ever increasing rate of livestock depredation and frequent sighting of leopards in the surrounding villages. Although the nature and intensity of the conflict varies from protected to non-protected areas.

The poor local population by no means can afford predating of their livestock because that’s mainly what they have. Most of them depend heavily on their animals for their sustenance and income. Eventually, the depredation is turned into retaliating killing of the poor beast.

But, the picture has another side too. Contrary to the general impression, Galliat leopards are normally human friendly animals, they do predate on animals but seldom attack humans. Since 1989, only 16 men have either been killed or injured in and around the Ayubia National Park, while in the same period 44 leopards have been killed either in self-defense or in retaliation.

A wave of retaliatory killing by humans started when in July 2005 one or more leopards killed five women collecting wood on the periphery of the Ayub National Park. The very next year, another woman lost her life in the same manner. These unfortunate incidents changed the mind of local people for ever and made them hostile towards the predator.

Now the questions are; where does the actual problem lie? Is an unending conflict between the two species is inevitable? Is retaliatory killing is nothing but the only and just answer? If not, then what? seeing the other side of the picture, we have to deal with some more questions as; should we turn a blind eye to the plight of the local people? And shouldn’t we stand against the increasing human infiltration, which is ruining the prospects of coexistence and natural harmony in the area on the one hand and further marginalizing the already subdued locals on the other hand?

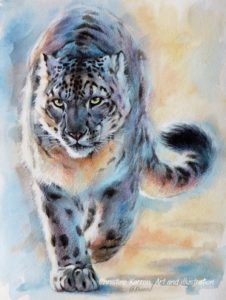

The common leopard is the jewel of our forests and one of the most precious national assets we have. A significant number of the leopards can help us in promoting our already fragile tourism. Instead of shooting this magnificent creature, we have to revive the lost relationship between man and leopard so that man and wildlife can thrive together in the same green lap of nature. Only an all inclusive conservation strategy is the answer to all the above questions. A strategy that can ensure an active participation of the locals in any development process and empower them to bring change in their lives. We can solve not a single problem without getting rid of that patronage style of politics which allows some people to predate freely on the well being of many others.

So, dear leopards start praying for the prevalence of rationality in your human neighbors because it is the only way to our survival.

Muhammad Atif Aleem, based in Islamabad, is a fiction writer and is in love with the leopards. His novella “Muskhpuriki Malka”, based on the human-leopard conflict in the backdrop of Galliat region is considered to be the one and only piece of fiction based on this sensitive issue.