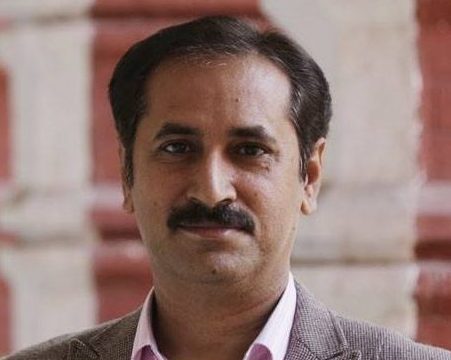

(Nasir Abbas Nayyar)

We are living in the age of narrative. Precisely speaking we are living ‘the age of narrative’. We hear narratives, speak narratives, read narratives, debate narratives, love and hate narratives and assimilate or disregard narratives. We are fettered by narratives.

To strive for freeing ourselves from narratives we have to work like Trojans to construct another narrative. It doesn’t matter whether we possess less or more theoretical knowledge of narrative. What matters is that we have or try to have one like a national identity card or passport. We have realised in some way or the other that it is only narrative that can prove us with a sense of identity.

We are least concerned about whether it would be reasonable or not to treat narrative as a ‘thing’. We have become prone to metamorphose everything into a ‘thing’, a consumable object, having only relative, temporal and short-lived value. Narratives are being treated like things that can be consumed or can serve some urgent purpose.

Paradoxically, a narrative is a little bit like a thing. Every idea or any abstract thing has some characteristics or the inherent potential of becoming a ‘thing’. Writing on ‘The Thing’, Martin Heidegger in Poetry, Language, Thought (1971) wrote: “everything gets lumped together into uniform distancelessness’’. Being an omnipresent entity, showing and showcasing on media, in academia, even at home, and becoming a ‘distanceless thing’, a narrative glowingly qualifies for being seen as a ‘thing’.

Mind the difference between being seen and being treated as a thing. Like a thing, a narrative can be exchanged. A narrative can be replaced by another narrative. Where there is a narrative, there is or must be another, resistance or alternative, narrative. All cultural wars are being waged in the field of narratives. And cultural war spread over from politics of identity to struggle for emancipation from all kinds of hegemony. Ghalib had said one and a half century ago:

جز سخن کفرے و ایمانے کجا است

خود سخن از کفر و ایماں می رود

(Where do exist disbelief and belief except Sukhan or Discourse, Discourse itself emanates from belief and disbelief.)

In simple terms faith and disbelief both are ‘narratives’. They can be proved or disproved only in narratives. All wars of Kufr and Iman are fundamentally waged in and through words that finally form a part of narrative of Iman or Kufr.

Narrative, originally a term of literary fiction meaning ‘oral or written account of events causally arranged’, assumed a metaphorical meaning in the 1960s, especially in the writings of Roland Barthes and other post structuralist critics. But the term has become more popular in the last few years. Its metaphorical import has overshadowed its original meaning. Its metaphorical import engulfs all kinds of oral ‘accounts’ or in writings. Narrative consisting of an ‘account’ must grab hold of some assumption(s) (i.e., events) and these should be logically (i.e., causally) organised.

Narrative as a term of literary fiction has never been considered a mime of true events, though it has to create an illusion of being a mime and pointing to some event as though it truly happened at some point in time and place. It is constructed. Both these things are glowingly visible in the metaphorical sense of narrative. Narrative can lead to some truth, an event, or points towards some truth but it itself is not a mime of any truth. Mind the difference. It is spectacularly constructed by some, in some language, for some purpose. Narrative in the metaphorical sense is an amalgam of narration and description. Standard description eclipses narration.

Every narrative has an inherent potential to be mimed and to stir up an opposing account simultaneously. Interestingly the mimetic aspect of narrative pushes for imitation while its descriptive feature encourages a process of understanding, debate, contest and finally opposition. So we have a new kind of narratives — resistance narratives. “Western people are enlightened and progressive”. “Muslims are extremists and enemy of scientific thinking”. “Women are intellectually inferior to Men”. “Pakistan came into existence in the name of Islam”. “Urdu is the language of Muslims of Subcontinent”. These are a few popular narratives we hear and read, accept and refute, assimilate and disregard.

The prospects of their resistance lie in the very construction of these narratives which start being revealed right from the moment the process of their comprehension and debate begins. The mimetic aspect of narrative seeks to put a stop to this process. Every narrative insists to be taken as a phantasm of reality and spurs people to believe it blindly and mime it uncritically. But as the process of understanding starts, phantasm goes into retreat and the ‘reality’ of narrative is surfaced which is actually a set of constructed assumptions that seem to be emanating from historical events or social truths.

Critical examination of a narrative always paves the way for a resistance narrative. In a way, a resistance narrative is bound to the narrative which gives rise to it. If one exists, the other or resistance narrative persists. Resistance narratives have played a crucial role in the process of emancipation but emancipation is only complete when alternative narratives are created.

Alternative narratives are new ones borne out of the process of asserting oneself in one’s own way. They are part of the course of achieving emancipation through creating one’s own knowledge in one’s own language, for one’s own people. Perennially resisting Others’ narratives is tantamount to wasting intellectual energies and building an imaginary prison for one’s intellect.

In modern age, a lot of sophisticated ways to control people’s minds have been invented. Control over means of constructing and disseminating those narratives that can incite opposition is the most sophisticated way to have power over people’s minds. Intellect becomes free only when it breaks the chains of Othering, a process that creates the illusion of recognizing the self through the Other, and suppressing its true function which is misrecognition. We misrecognise ourselves through or by Others but live the illusion of being recognized by them. Creating an alternative narrative means to start living one’s own life by utilizing one’s own resources for one’s own purposes.

Alternative narrative doesn’t form an alternate for some specific narrative but narrative itself. Forming alternative narratives means to capture the source of one’s own creativity, a land that can be discovered by none other than us.

Published in The News on Sunday, on August 21, 2016